…Within the Small Blocks, buildings must be organized in relation to outdoor spaces for various functions.

__Problem-statement: Within a block there is a need for outdoor space which is connected to the buildings, but not to the street.__

Discussion: Residences require outdoor space for recreation, for gardening, for parking and other needs. Commercial users also need outdoor space for utilitarian functions and service access. If this space is between the building and the street, it will cut the building off, and probably damage the experience of walking on the street. Putting it behind, inside the block and with buildings forming a perimeter, solves this problem, and offers other advantages.

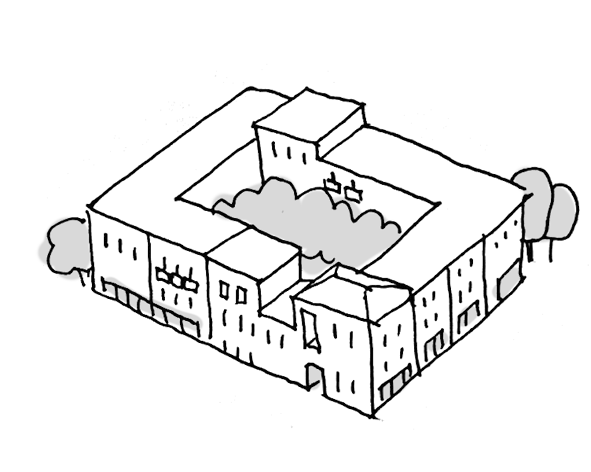

The perimeter block arose independently in different civilizations over millennia as a naturally economical and practical urban typology. One important advantage is that buildings benefit from proximity to the walkable streetscape, and at the same time get ample light and adjacent private outdoor space in the quieter and more secluded interiors of the blocks.¹ Another benefit is that the perimeter block saves energy by clustering the buildings along the perimeter, and by facilitating a low-tech passive solar orientation, especially when exploiting deciduous trees and other near-ground benefits.² In addition, enclosing a gradient of small private gardens, parking courts and utilitarian spaces in the rear keeps the street intact for more public uses, and helps to frame more active, better-quality streetscapes.

Nevertheless, perimeter blocks fell into disfavor by industrial-modernist planners, who favored a very different typology: the apartment “slab” tower set in a large, undifferentiated green space. From an urban point of view, this is exactly the wrong geometry: the seldom-used green space is outside, separating buildings from streets and creating amorphous, unwalkable and often dangerous zones that Jane Jacobs memorably called “project prairies.”3

This contradiction is due to a misunderstanding of human psychology, which requires comfortable space to be defined by boundaries, and not left too open. It is also at the heart of the switch from traditional design — where buildings help to define urban space — to using open space instead to define a stand-alone building.

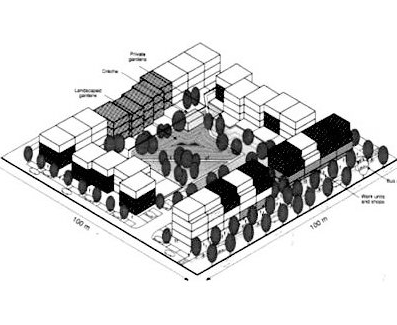

A very flexible perimeter block with a mix of uses, as proposed by the UK’s Urban Task Force (1999).

A perimeter block has the right sequence of public and private space: well-activated streets with close-grained private spaces in tight spacing; buildings that look out onto the streets; and then private outdoor space for gardening or utilitarian uses. Parks are where they should be: frequently distributed in lively locations. The entire perimeter block structure facilitates a greater mix of uses and grain of streetscape.⁴

__Therefore: Place the bulk of building mass at the perimeter of the blocks, leaving the interior for outdoor space to serve the adjacent occupants, accommodating recreation, gardening, parking, service and other functions.__

Use the Perimeter Building pattern at the edges of the blocks. Use Layered Zones and careful transitions from public to semi-private to private, and again to semi-private in the courtyards. …

notes

¹ One of the most thorough discussions of the perimeter block and its benefits is in Carmona, M., Heath, T., Oc, T., & Tiesdell, S. (2012). Public Places-Urban Spaces. London: Routledge.

² See for example Vartholomaios, A. (2015). The residential solar block envelope: A method for enabling the development of compact urban blocks with high passive solar potential. Energy and Buildings, 99, 303-312.

³ There has been much debate and research on the safety of such spaces. The architect Oscar Newman famously argued for “defensible space” rather than open park-like spaces. UCL’s Bill Hillier presented evidence that the picture is more complex, and that an overriding problem is the lack of “co-presence” of others and natural surveillance from buildings. See for example Hillier, B., & Sahbaz, O. (2008). An evidence-based approach to crime and urban design. London: Bartlett School of Graduates Studies, University College London.

⁴ Urban Task Force (1999). Towards an Urban Renaissance. London: Routledge.

Image: Kaspars Upmanis via Unsplash

See more Block And Plot Patterns