…We need to establish a settlement area as it relates to a wider regional structure. This pattern governs the relation of urban centers to their peripheries.

__Problem-statement: Cities that are too centralized too often require excessive commuting from their edges, and their cores can become unhealthy monocultures.__

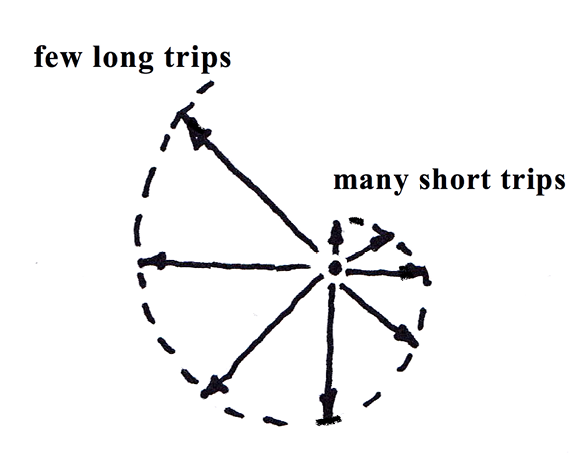

Discussion: We can see that where cities and towns have developed in a more natural pattern — especially prior to the automobile — there has been a remarkably regular distribution of city sizes, with a few large urban centers, many smaller satellite towns, and a medium range of mid-size settlements, often suburban town centers. Similarly, most residents in these areas make a great many short trips — for example, daily trips to a nearby grocery store or to school — as well as a few long trips, perhaps to a major cultural event in another town. In between these extremes, they make a medium number of medium-size trips — for example, trips to work. This range of trip lengths could be illustrated this way:

But when a city is too centralized, even routine trips can become long commutes — for example, when the center is a monoculture of offices and workplaces, and the edges are primarily residential. By the same token, a city can also become too decentralized, with too many resources scattered across a large region, and requiring too much energy and cost for most people to access equitably.

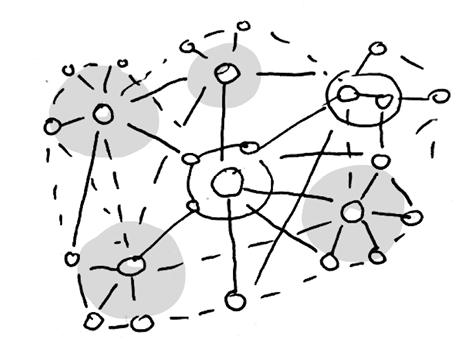

A healthier pattern will include a more optimum distribution of activities and uses across settlements and scales, forming a “polycentric” region — a region with a range of diverse, mixed centers at a range of scales, each of which offers most of the routine destinations, activities and amenities of urban life.¹

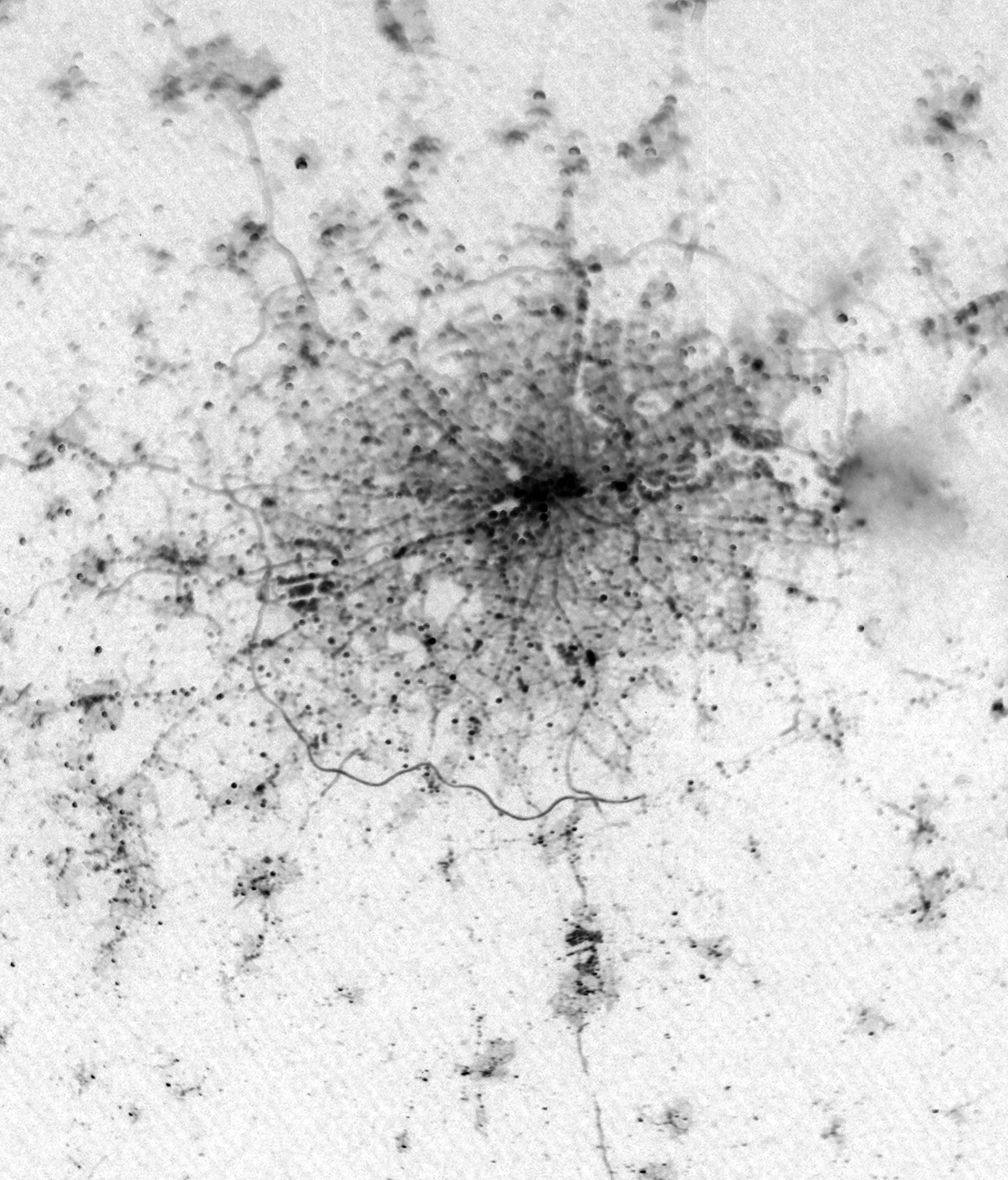

This pattern can be seen clearly in the example of the London region (the photograph for this pattern). There a series of “urban villages” offers most of the needs for most residents to live, work and play within their own area, while they can also take longer trips less frequently. Some may make long frequent trips, but many do not.

This pattern also extends to the smaller cities and towns of a larger region. Their residents also need to be connected to the same regional economy, with similar life opportunities and exchanges, but focused more on the activities that are best suited for their regional location — for example, industries needing regular access to rail, water-intensive industries, or other location-specific economic activities.

What we describe goes to the heart of stable sustainable systems, which as evidence suggests, obey “fractal” scaling properties.² That means there are a few big elements, many small elements, and a medium number of medium-sized elements. In the case of path lengths, the same is true: there must be many more short trips, and many fewer long trips, made possible by the geometry of the urban fabric and its distribution of uses. Unfortunately in the 20th century, we created urban forms that forced too many longer trips, largely by separating functions with zoning. That was not a stable or sustainable condition.

All of these nodes in the local, regional and even global network, need to be well-connected and well-developed to provide balanced life opportunities for all residents. Evidence shows that when some populations are cut off from genuine opportunity for growth and human development, there are political, economic and environmental impacts for all populations that are likely to become unsustainable over time.

__Therefore: Develop cities as nodes within polycentric regions, consisting of a range of sizes of mixed, diverse, well-connected “urban villages” that offer a full complement of daily and weekly needs, and good access to other parts of the region for less frequent trips.__

Establish a rough structure of a 400M Through Street Network, creating continuous walkable and multi-modal urban areas. Where interruptions occur, such as natural geographic obstructions, connect the centers as much as possible with a continuous network, organized around the Mobility Corridor and Multi-Way Boulevard patterns…

notes

¹ See for example the special issue of Urban Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, and in particular the introductory essay, Kloosterman, R. C., & Musterd, S. (2001). The polycentric urban region: towards a research agenda. Urban Studies, 38(4), 623-633. Available on the Web at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00420980120035259?casa_token=UN34U0vUJnMAAAAA:pIlcW55gb7HLO_J7IX8iPbyC3ASwQYp9oiBTjJtpcW1Hvyk7qu1s3rjBJj8q6aTUrfof-OuStj-a

² See for example Salingaros, N. (2005) “Connecting the Fractal City,” in Principles of Urban Structure. Amsterdam: Techne Press. Available online at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.431.6038&rep=rep1&type=pdf

See more Regional Patterns