…Within the Polycentric Region, there are many places where industrial activities must be accommodated. These should be integrated into the walkable street...

__Problem-statement: Industrial employees increasingly want to work in vibrant, mixed neighborhoods. But industries need a certain amount of security and privacy for their operations.__

Discussion: Well-meaning planners reacted to pollution within early industrial cities by relocating all industry outside the city. But that move threw out the baby with the bathwater: it forced employees to commute long distances, and created isolated, lifeless districts. Today, only genuinely heavy industry needs to be accommodated outside. Most other light industrial activities fit well within a mixed-use city (with air and water quality protected by enlightened regulation). This mixing of work and life is the way that cities have thrived for millennia. Mixed use also facilitates commuting to work, and is one of the cornerstones of a new conception of the city as a complex system: the functions cannot be simplistically segregated without damaging it.

A new rationale for segregation in the 20th century has been security, especially security of trade secrets. This has given rise to the “supercampus” — a very large, gated, and impenetrable section of the urban (or more often suburban) fabric. This has been a terrible mistake, creating dead zones at the edges of these supercampuses, and almost always preventing employees from walking, biking or even taking transit to or from work — more likely forcing them to drive, and therefore to own a car. Even worse, this supercampus model further isolated work from home and other activities, causing an imbalance between jobs and housing, requiring extensive commuting time, and contributing to a fragmented, resource-inefficient, dysfunctional city.

In the early years of the 21st Century, the most sought-after employees have begun to demand more walkable, mixed places of work, closer to their homes and other destinations, and the supercampus is rapidly losing its competitive edge. More companies have begun to integrate their buildings into the urban fabric of walkable “innovation districts” and other creative neighborhoods.¹

Evidence has grown that there are significant economic benefits for the companies as well. Creative innovation does not thrive in isolated, inward-turning campuses, but in places that allow mixing and “knowledge spillovers” — not only within industries, but between them as well, and within the public spaces surrounding them.

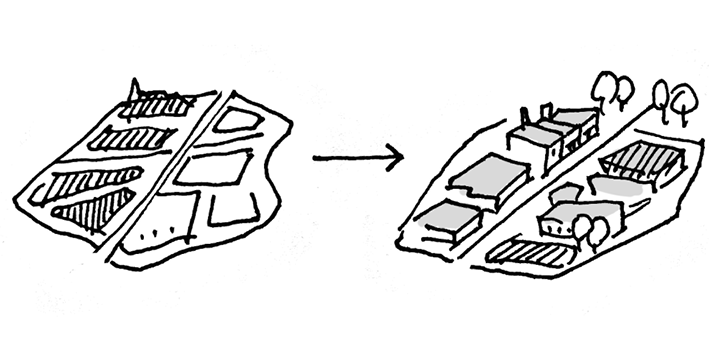

Left, an industrial “supercampus” outside of Portland, Oregon, and right, an industrial district within the city. Walkable mixed neighborhoods like the one on the right are in high demand by today’s most sought-after technology employees.

Of course there are requirements to protect intellectual property as well as other kinds of company property. However, in an age of advanced digital security, it is no longer necessary to have prison-like guard houses and fortifications, and security is now much more easily managed at the building scale. Employees can now move securely between buildings with proper digital technology.

__Therefore: Do not build isolated “supercampuses” as industrial workplaces. Instead, create a flexible cluster of buildings within a walkable street system, mixed with other uses so that employees can live nearby, and visit other destinations.__

Provide a Walkable Streetscape within the industrial area, with a mix of other uses to provide amenities and close-by housing for some employees…

notes

¹ Notable research on this trend and its dynamics has been done by the Brookings Institution. See for example Katz, B., & Wagner, J. (2014). The rise of innovation districts: A new geography of innovation in America. Washington: Brookings Institution.

See more Special Use Patterns